Month: June 2017

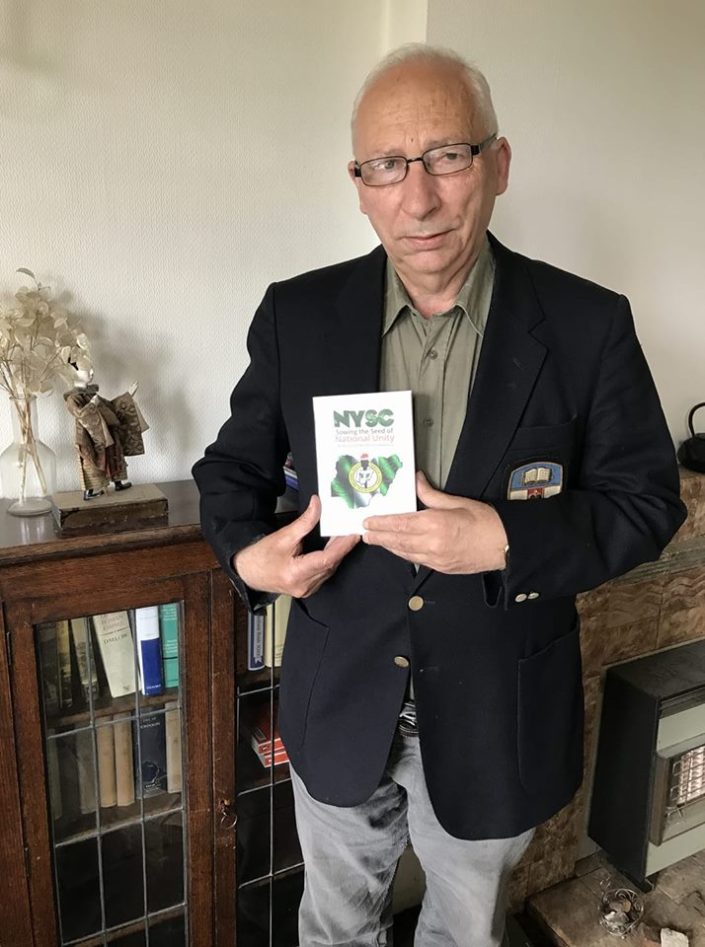

REVIEW: NYSC Sowing the seed of national unity

Reviewed by Dr. Frank O’Reilly

The National Youth Service Corps (NYSC) is a body that will be known to most Nigerians and expats who have worked in Nigeria. Established in the early 1970s, it was set up so that graduates could render ‘a national service’ to the nation’s economy, often at local government or federal level. Though having a khaki uniform and perhaps militaristic-style rituals, it is not a national service in the sense that we find in other countries where youth are called up as a defence force. An important aim also was national unity – corpers were often posted to distant parts of the country. I suppose a third benefit was that it temporarily eased the problem of graduate unemployment.

This short book by Stephen Akuma, a lecturer in maths and computer science at Benue State University, is not a political, economic or historical analysis of NYSC, though such a book is needed. Rather it is a partial autobiography of one corper, though actually it is the NYSC rather than any individuals that holds centre stage and all the characters seem to dance around it like marionettes.

A few words are needed on my own connection with this. I was introduced to the author by my old friend, Prof. Isaac Yongo of the innovative Department of Linguistics at Benue State University (who wrote a succinct Foreword to this book). I discussed part of the early manuscript as well as marketing strategies with Stephen. When the book was finished, he asked me to review it and help in publicity.

I learnt a lot from my reading here about NYSC from the inside, as previously my observations had been rather superficial. I had heard anecdotes about how ‘rich kids’ could get good postings, whilst for others in distant bush schools conditions could be hard with corpers sleeping on their desks because of lack of accommodation. The potential for culture clash was ever present. One Tiv man told me his Yoruba pupils had asked: ‘Which country do you come from, sir?’ A young Fulani man dressed up in his finest babbanriga caused the little children of a Delta village to flee in fear, thinking they had seen a phantom. Nor should we underestimate the importance of diet. My own research in the 1980s had demonstrated how ‘tied’ the ethnic group was to its particular carbohydrate staple. An Igbo simply could not imagine eating the Hausaman’s gero (millet). But rice was the somewhat expensive unifier of taste.

Akuma does not dwell on the hardships of corper life, but the ethnic issues are on almost every page. The book is divided into two parts. The first part deals with the training, when friendships and perhaps rivalries are forged and ‘boy meets girl’, though in this story it seems that ‘boys meet girl’. The second part is about the author’s time in the Police Academy in Kano state. In both cases the eccentricities of speech and behaviour of different groups are amusingly delineated – but in an amicable manner – because when a person steps out of line or quarrels the question arises:’ What is his tribe? What is his religion?’

Apart from enjoying the book as a whole, I could relate to the recognisability of the narrative. This is because I worked in Kano for several years and, in teaching and research, became familiar with Hausa culture. Secondly, through my friend, Isaac Yongo, I became acquainted with the Tiv community. Nigerians from the South or expats who spent their working careers in the southern states of Nigeria might find the local colouring of the story a bit less penetrable, but, hopefully, they will relish the general principles.

The author admits his service helped him overcome two major prejudices. First of all, he was afraid of Kano State and apprehensive about Hausa-Fulani people in general. Such a prejudice is widespread not only in Nigeria but among many of the Nigerian migrant community and their children in the UK, where it is extremely rare to meet Hausa people. He devotes much of one chapter (entitled ‘I met a Hausa/ Fulani man’) to this. He discovers: ‘[they] are good people who [in you] see another human being; they are honest, sincere and simple.’ However, when he explained his new views to a (possibly southern) friend, the response in pidgin was: ‘Dem no open eye’, meaning they are not ‘open-eyed and smart.’ Incidentally, there is a sizeable amount of pidgin and vernacular expressions in the story, thankfully mostly explained in the useful glossary. Some critics might think these ‘foreign dialects’ slow down reading and comprehension, but it would be totally inauthentic and weak to have the characters conversing in the Queen’s English. To paraphrase Marshall McLuhan, the dialect is the story. The way that characters switch from one language register to another depending on the context is also completely realistic. Even highly educated people use pidgin in relaxed familiar surroundings ‘among friends’, whilst Hausa is par excellence the language of emphatic sincerity.

The writer’s second prejudice is the one most students have towards the police force but he concludes ‘they are our friends in the mutual fight against crime.’ On the personal level they are just trying to do a job and survive, having wives and children to support.

In this book there are ‘good ogas’ and ‘bad ogas’ but the bad ones are not cruel and immoral. Rather they are strict disciplinarians and stick to the rules. The ‘good ones’ seem to be the more laid-back and flexible bosses, who are prepared to allow minor indiscretions. In fact here we will find no heroes or villains. Even the corpers are seen as tricky: they are absent without leave; they tell lies to get the better postings; they haggle over remuneration; some seem to be constantly complaining; snitches and spies are on the look-out; they are good actors and use melodrama to get what they want – the image of a corper prostrate hanging on to a Co-ordinator’s leg and pleading for ‘justice with mercy because of God’ is one that has lodged in my brain.Yongo writes in his Foreword: ‘I could see the events taking place before me’; so could I. They are all authentic recognizable human beings and all identifiable as Nigerians. As the German philosopher Nietzsche put it: Human, all too human!. In fact I would imagine some, especially the officers, might recognize themselves in this book, whether or not their names have been altered.

As I said, this is not an analysis, but the narrative can point to analysis. One question might be: Are the corpers really doing a useful job that benefits the community? The author does not touch on this directly, as his focus is on the corpers’ experience not the experiences and views of those ordinary people the corpers might serve. However, the writer, although theoretically a trainee, became ‘because of high proficiency with the use of the computer’ largely responsible for managing electronic electoral registration over a large area. There is also promotion within the NYSC: diligent corpers become liaison officers. I have no doubt also that corpers in all those bush schools (that Nigerian and expat teachers avoid) are essential to keep the education system viable. What I do not know is whether the service has any impact, direct or otherwise, on the corpers’ later employment.

Yongo argues that the book should be required reading for new corps members and Akuma points out at the end the great value of NYSC when people ‘called for scrapping it.’ So the market for this book is mainly within Nigeria. I do feel however that expats with Nigerian experience, ‘Nigerian societies’ in the UK, such as the Nigerian Field Society and the Britain-Nigerian Educational Trust, departments of African studies in Western colleges and faculties of education and social policy everywhere would benefit from this book.

It is quite unusual for a mathematician to be a creative writer but Akuma has this flair and I hope that other books will follow. I even think this highly entertaining and dynamic narrative would make a great movie. Credit should also be given to Terna Stephen Igyeri who designed the arresting cover picture.

The book was written in 2015 and described events from 2006 to 2007, yet I could recognize the Hausaland of the late 20th century in its pages, although Akuma’s narrative would have been quite different in a society with very few computers and mobile phones. However, arguably, now Nigeria and the North in particular are very different places: ethnic and religious differences have hardened; there appears to be more insecurity and communal violence; the word ‘terrorism’ is used; Nigeria is on the BBC in a way that is has never been before and this is not, unfortunately, good news. So now more than ever there is a need for books, acceptable to all, that foster peace and harmony, that, like the NYSC itself ‘sow the seeds of unity’, even if the harvest seems distant.

Therefore I unreservedly recommend this book to anyone who has an interest in modern Nigeria. My final commendation would be the Hausa expression of admiring surprise: Wayyo!

For more information about the book, visit: https://sacs945.wordpress.com/book/

TRUTH 101: The Nigerian Constituent parts

The cup you are about to taste (read) is bitter. If you are allergic to the truth please don’t read this post because it will offend you.

The Nigerian constituent parts:

THE “CORE” NORTH

They always want to lead and they believe that they can’t be economically buoyant without controlling the political paraphernalia of government. Their first priority is to have a Hausa/Fulani Muslim as President or leader, and then any other thing can follow. At the moment, they are aggressively mending the northernised-chain that was broken by GEJ and OBJ’s governments. Their sole agenda was to ensure that a “core” Northerner becomes president and then revamp the Ahmadu Bello’s northernisation policy.

Considering that desertification is encroaching in most part of the “core” North and they are not certain about the future of Nigeria, they are currently trying to expand their territory by capturing towns and villages within the Middle-Belt so that in case the bond holding Nigeria fizzles out, they will not face famine like Niger and Chad. You will recall that the 1804-1807 Jihadists could not conquer the Middle Belt territory after conquering the Hausas.

THE SOUTH WEST

The South-West are not really interested in the state called Nigeria. They got this training from Awolowo who openly said: “I am a Yoruba man before I am a Nigeria”. Once you settle them with juicy political appointments, they will tame their attack dog (Lagos-Ibadan press) and play game with whoever is in power. In the present dispensation, they control all the “juicy” ministries (Finance, power, works, housing, communication etc). The effect of this is that over 80% of the contractors of these ministries will be Yorubas and this will boost the economy of the region as more Yoruba youths will be employed by these contractors. Same thing happened during Gowon’s regime. Gowon was young and inexperienced when he handed over the economy of Nigeria to Awolowo to manage. Awolowo through his privatisation policy sold almost all the FG government properties in the South West to his people. Some of the FG properties in Lagos and Ibadan became part of Oduduwa investment.

THE MIDDLE-BELT

The Middle Belters are neither here nor there. They are like bats, always used by the “core”-North for population and strength and war. They accept the name “Northerners” because they still consider the “core” North a lesser evil as compared to the Southerners. When J. S. Tarkaa began a movement to unite the northern minorities under one name, some of the minority tribes sold out to the ruling NPC government. J.S. Tarkaa was then left alone in the middle of the struggle to lick his wounds. His people (Tiv) are still suffering the consequence of his doggedness. In the Nigeria of today, they have been alienated and stripped off of any government appointments even though they are the 4th largest ethnic group in Nigeria. The Tiv people are also to be blamed for their woes; politics has sown a seed of discord among them. Their disunity fastens the whip of their oppressors. For instance, If not for Agatu massacre and the quick response of the Idomas, the world wouldn’t have known that there is a genocide going on in the Benue valley.

THE SOUTH EAST

The Igbos are the most unorganised ethnic group in Nigeria. They are not united but appear to be united on social media. A region where some of their people are referred to as outcast (osu) and some (Nngwa and Mbaise) are considered as bad people and some (Abakalika) are considered unmarriable tells a lot about their disunity. Their love for money is one of their greatest undoing and the reason for the distrust among them. Perhaps the monetary trait is one of the effects of their struggle for scarce resources after the civil war.

They are the ones preventing the bond between the minorities in th North and those in the South. The South-South and the Middle Belt believe that they can come together and form the fourth leg of the Nigerian table but the Easterners always try to use the old Biafra map to work against this bond which is targeted at scuttling the tripod arrangement of Nigeria.

THE SOUTH-SOUTH

They own the oil resources of the nation while the Middle Belt owns the food resources of the nation. Without these two regions, Nigeria will starve. The South-South are quiet about the happenings in the country because their own son ruled for 6 years and could not do anything for them, making their years of struggle for the presidency a wasted effort. He could not complete the East-West road, build any major air or sea port, reduce the oil spillage and gas flaring, clean up Ogoni land and ensure that the PIB bill is passed into law. As they try to protect their son (GEJ) from public ridicule, they silently lick their wounds and mourn the wasted opportunity. A coalition/synergy between the South-South and Middle-Belt will protect the two zones feeding the country from the constant marginalisation by the majority tribes.

As you can see, Nigeria is an assembly of different ethnic nations; only true federalism can redefine our friendship and build a lasting peace.